Introduction to path tracing

Published:

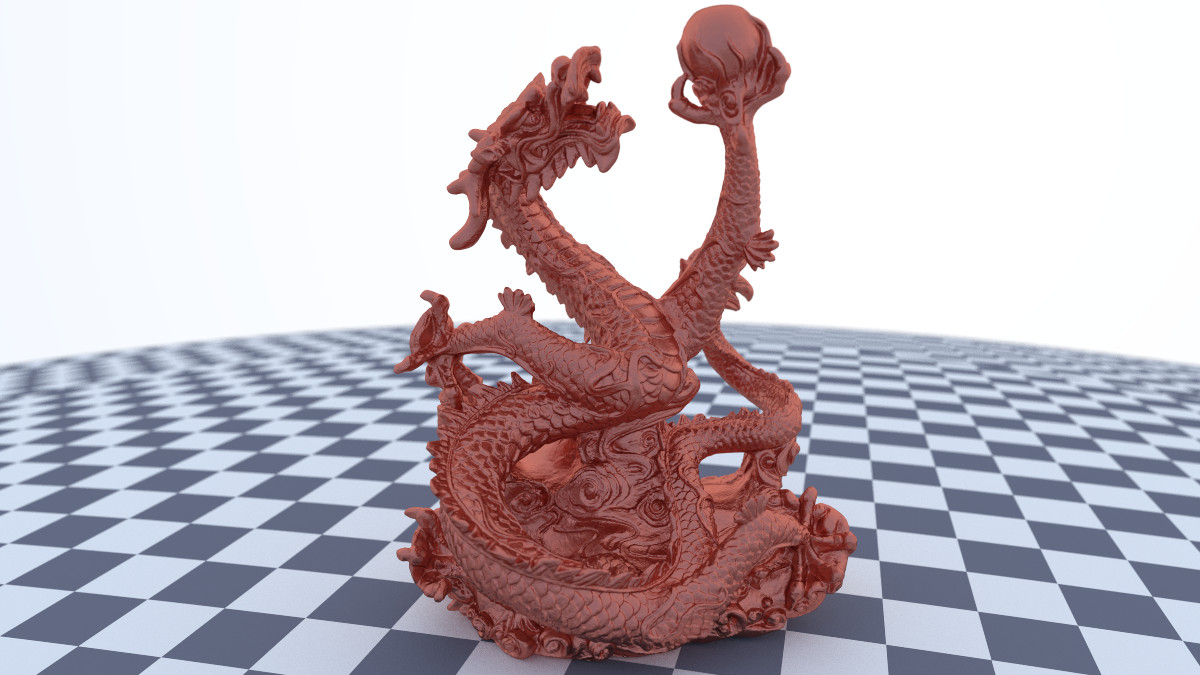

Path tracing is a technique in computer graphics (in the ray tracing family) for rendering a 3D scene by tracing along the individual paths taken by a random ensemble of photons travelling from light sources in the scene to the camera.

As a holiday project this year, I decided to implement a basic path tracer from scratch, following along with the awesome book series, Ray Tracing in One Weekend by Peter Shirley, Trevor David Black, and Steve Hollasch. Credit goes to these authors for most of the code in my project; however, what follows is my own presentation of the concepts involved.

Download: GitHub repo

Basics of ray tracing

Ray tracing begins with a 3D scene to render. The scene comprises a bunch of geometric objects, called “primitives”, such as spheres, triangles, etc. The primitives each store their geometry, in the form of vertices, lengths, angles, normal vectors, etc - whatever makes most sense for each primitive - as well as their material, which dictates their colour, and more generally how light interacts with them. Before we can render anything, we must first define a camera to capture the scene.

Camera model

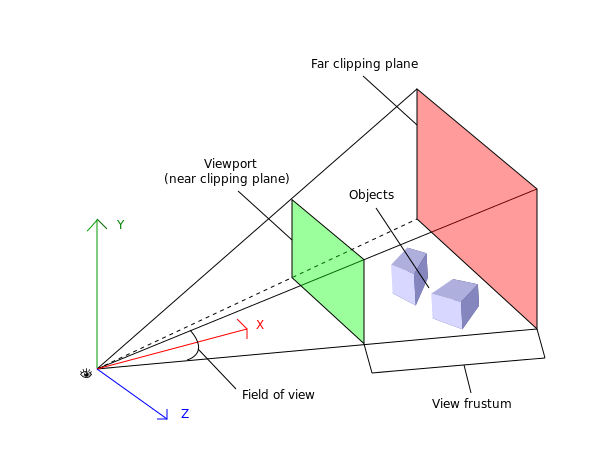

The basic camera model camera comprises a centre and a viewport (which together define several other parameters, such as field-of-view, focal distance, and aspect ratio). We define these parameters as follows:

- Embed a rectangle in the 3D scene to serve as the camera viewport. The viewport’s dimensions should be in the same proportion (“aspect ratio”) as the desired image.

- At a fixed distance, the “focal distance”, along the perpendicular line through the middle of the viewport, mark a point \(\mathbf{c}\in\mathbb{R}^3\) as the camera centre.

We imagine our camera ‘looking out’ from its centre through the viewport towards the scene, so that the centre and viewport together define the camera’s “view frustum”.

For our purposes, the far clipping plane of the view frustum is at infinity.

Rendering the scene

With a camera situated in the scene, we can now render an image from its perspective. The most basic version of the ray tracing algorithm proceeds as follows:

- Map the image pixel grid onto the viewport. In other words, divide the viewport into a grid with dimensions matching those of the desired image.

For each pixel, \((i,j)\), on the viewport, construct a ray, \(\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t)\), originating from the camera centre \(\mathbf{c}\), and passing through the centre, \(\mathbf{p}_{ij}\), of the pixel, toward the scene. This ray has equation

\[\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t) = \mathbf{c} + t(\mathbf{p}_{ij} - \mathbf{c}),\quad t\geq 0.\]- For each primitive in the scene, solve for the values of \(t\geq 0\) at which \(\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t)\) intersects the primitive. Keep track of the closest (smallest-\(t\)) intersection and the primitive involved.

- Once the closest ray intersection overall has been found, use the primitive’s material to look up the object’s colour at the intersection point and set the output pixel to that colour.

Here is some pseudocode for the basic algorithm:

for each pixel

initialise t_min to infinity

initialise hit_object to none

get ray from camera centre to pixel

for each primitive

if ray hits primitive at t < t_min

update t_min to t

update hit_object to primitive

if hit_object is none, set pixel to background colour

else, set pixel to colour of hit_object at ray(t_min)

Additional comments

Here are some additional comments on the above algorithm:

- How ray-object intersections are calculated will depend on the geometry of each primitive. For spheres, and planar shapes like triangles, it is straightforward algebra, but it can get complicated in general (for a torus, it requires the quartic equation!).

- Aside from solid colours, materials can also have a position-dependent texture (such as a colour gradient, image, or random noise function); in such a case, we need to map the intersection point, \(\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t_\text{int})\in\mathbb{R}^3\), to 2D texture coordinates \((u,v)\in[0,1]^2\) to look up the correct colour at the intersection point. How this is done will again depend on the geometry; it amounts to a choice of local coordinates on the surface of the primitive.

Path tracing

The basic algorithm above assumes that the colour of each point on the surface of an object can be found in isolation, independent of surroundings. This is, of course, wildly inaccurate in reality. Objects can be in shadow, or lit by coloured light, or reflective, or transparent. To handle such cases, we must update our algorithm to track the complete paths taken by light rays as they bounce around the scene, all the way from light source(s) to the camera. This change distinguishes path tracing from more basic forms of ray tracing, and it allows us to simulate most real optical phenomena like reflectance, refraction, and even polarisation.

The code changes required to the main loop are surprisingly minimal, because

- we invoke Helmholtz reciprocity to justify continuing to trace paths “backwards” (from the camera towards the scene), as this way we guarantee that each path intersects the pixel we are trying to colour; and

- we still query the material for the colour at each ray intersection point, only now, in order to determine this colour, the material may opt to scatter the incoming ray first, recursively obtaining the colour of the scattered ray.

Getting the ray colour

To expand upon the latter point, the material decides the colour of the incoming ray using something like the following procedure:

- If ray is absorbed (randomly decided, based on material’s albedo) output black.

- Else, if material emits light, add that to the output colour.

- Determine if / where the incoming ray is scattered:

- If material is transparent, decide between reflecting & refracting, with probability based on the reflection coefficient in the Fresnel equations.

- If refraction occurs, use Snell’s law (with refractive index of material, and surface normal at the intersection point) to get the scattered ray.

- If reflection occurs, flip the incoming ray about the surface normal, and reverse its direction to get the scattered ray.

- Else, if material is reflective, reflect as above.

- Else, if material is matte (or partially so), scatter in a randomly selected direction (sampled from some probability distribution on the hemisphere of outgoing directions).

- If material is transparent, decide between reflecting & refracting, with probability based on the reflection coefficient in the Fresnel equations.

- If scattering occurred, recursively obtain the colour of the scattered ray, multiply it by the colour of the material (which, remember, can depend on a texture), and add the result to the output colour.

Most of the complication of a path tracer lies in this routine. Much of that complication lies in correctly defining and sampling from the probability distribution on the direction of scattered rays, known as the bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF). Matters are made worse when we start artificially modifying this distribution to get faster convergence (see the section below on Monte-Carlo integration).

Bounce & sample limits

A consequence of materials randomly deciding if/where to scatter rays is that, over many bounces, initially-identical rays end up taking vastly different paths. As such, it no longer suffices to fire a single ray at each pixel. To get an accurate image, we need to fire many rays (“samples”) at each pixel - the more the better. We are of course limited by computation time; this algorithm gets slow quickly.

Another constraint we impose to bound execution time is an upper limit on the number of ray bounces (ie. the recursion depth). Again, the higher we set this limit, the more accurate our results will be.

Complete path tracing algorithm

Here’s the rough algorithm so far then:

procedure render()

for each pixel

initialise pixel to black

for each sample

get ray from camera centre to pixel

update pixel by adding ray_colour(ray) / number of samples

with the subroutine

procedure ray_colour(ray)

if recursion depth exceeded return black

initialise ray_colour to black

initialise t_min to infinity

initialise hit_object to none

for each primitive

if ray hits primitive at t < t_min

update t_min to t

update hit_object to primitive

if hit_object is none, return background colour

if hit_object material emits light

update ray_colour by adding emitted light

if hit_object material elects to scatter ray

get scattered_ray from hit_object material

update ray_colour by adding hit_object material colour * ray_colour(scattered_ray)

return ray_colour

Extending the camera model

As it stands, our camera will capture an image with objects projected onto the image plane by a perspective projection (ie. distant objects appear smaller), and all objects perfectly in-focus. In this sense, our camera is behaving as an ideal pinhole camera, rather than an actual lensed camera. Lenses add a number of interesting (often aesthetic) optical effects to the image, such as distortion (think fisheye lens), blur, and lens flares. There are several modifications we can make to our ideal camera setup in order to mimic these and more effects.

As a simple example, if we wanted an orthographic projection of the scene, rather than a perspective projection, we would simply ditch the camera centre, instead projecting rays directly from each pixel on the viewport, directed orthogonally to the viewport.

Focus & depth of field

Another simple modification allows us to emulate focus. For this, we create a disk, called the defocus disk, centred on the camera centre and parallel to the viewport. Then, each time we generate a new ray, we originate it from a randomly-sampled point on the defocus disk, instead of the camera centre. Averaging a number of such rays per pixel results in a nice blur effect.

Objects at the focal distance from the camera centre are perfectly in focus, and everything else is blurred to a degree dependent on its distance from the focal plane (in this case, the plane of the viewport), as well as the radius of the defocus disk (relative to the focal distance). The range of distances at which objects are acceptably in-focus (we precisely define “acceptably in focus” by constraining the allowable radius of the so-called circle of confusion produced in the image by a point-like light source in the scene) is called the depth-of-field. This is all standard terminology in photography.

Bounding volume hierarchies

One of the most computationally expensive steps of the path tracing algorithm is testing for ray-object intersections. For each ray, we loop over every single primitive in the scene; this includes primitives which are behind the camera, or else really far away from the given ray. When rendering, say, a 3D mesh composed of hundreds of thousands of triangle primitives, these spurious tests become prohibitively expensive.

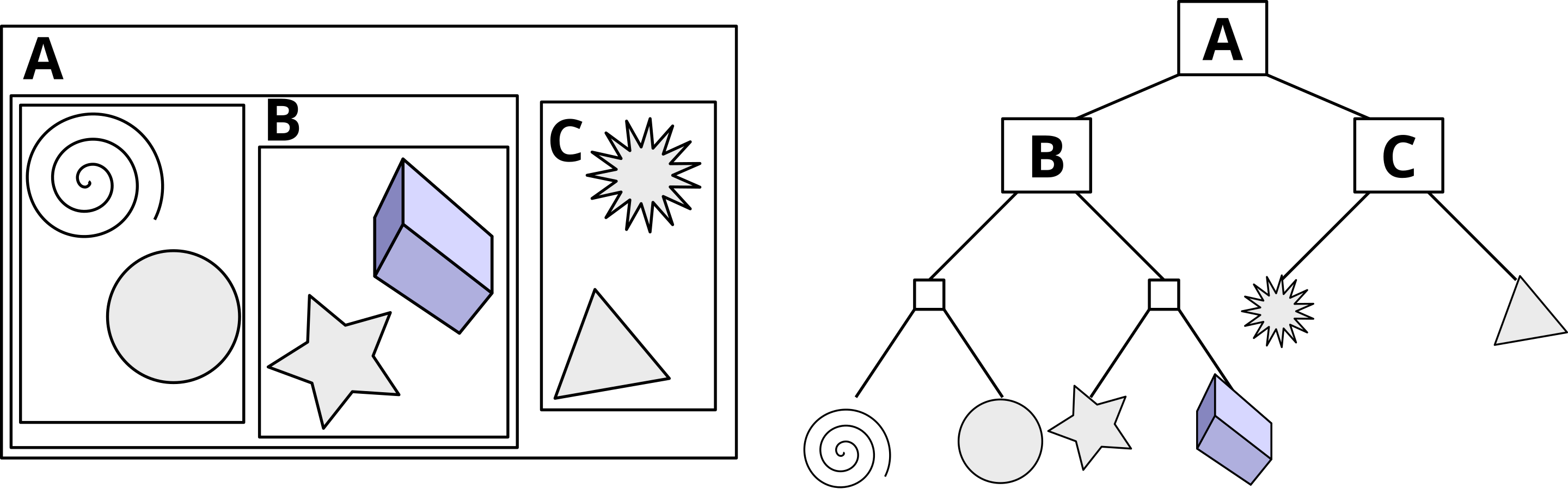

As such, one of the most significant optimisations we can implement is a way to reduce the number of intersection tests needed per ray. This is achieved by spatial partitioning; in particular, a tree data structure called a bounding volume hierarchy (BVH).

Overview of BVH

The idea behind a BVH is as follows:

- First, we give each primitive a bounding box. This is just an axis-aligned rectangular prism enclosing the primitive. Now whenever we test a primitive for intersection with a ray, we first test whether the ray hits the bounding box (which is cheap), and if not, stop immediately.

- Next, suppose our scene contains two objects, each enclosed by bounding boxes. Prior to rendering, we can, at little computational cost, compute and store the combined bounding box enclosing both objects. Given such data, we are then able to short-circuit several intersection tests - those involving rays that miss the combined bounding box - without testing against each object individually.

- For scenes containing more than two objects, we apply this concept recursively. That is, we build a binary tree from the scene, where each node is a bounding box, and the left and right children of each node are bounding boxes that are strictly contained in their parent. Then, to test for ray intersections, we only check intersections against child nodes if the intersection test against the parent node passes.

Here’s a visualisation of a BVH in 2D, courtesy of Wikipedia:

In the best case, this makes ray-object intersection tests logarithmic in the number of objects in the scene, rather than linear - a massive improvement! However, for this to be completely effective, we must attempt to ensure that the left and right child bounding boxes of each node overlap minimally; otherwise, we will often end up needing to check intersections against both children anyway, saving no time at all.

BVH construction

Here’s how we construct the BVH then, taking care to ensure minimal overlap between child nodes, as discussed above:

- Start with a single root node, containing a list of all objects in the scene.

- Compute (and store) the bounding box enclosing all objects in the current node. Compute its longest axis. Sort the contained objects in order of their (bounding boxes’ lowest) position along this axis, and bisect the sorted list.1

- Create two child nodes, assigning one half-list to the left, and the other to the right. Recursively apply step 2 to each of the child nodes, terminating on the base case of a node containing a single object.

Affine transformations

When creating our scene, we obviously want the ability to move primitives around in space, as well as rotate and scale them. More generally, we would like the ability to apply an arbitrary affine transformation to them; that is, a map of the form

\[T\colon\mathbf{r} \mapsto M\mathbf{r} + \mathbf{b},\]for some non-singular matrix \(M\in\mathrm{GL}(3,\mathbb{R})\) and shift vector \(\mathbf{b}\in\mathbb{R}^3\).

In some cases, it may be possible to apply such a map to all vertices of a primitive once, prior to rendering, then save the result and render as usual. That’s all good and well for primitives like triangles, but often things are not so straightforward. Consider a sphere, for instance: internally, it stores only a centre and radius. It’s not clear therefore how we might store its image under a transformation. A similar problem arises whenever we have a primitive whose image under a transformation cannot itself be represented using any primitive. The more general solution is to instead apply transformations as part of the ray intersection computation.

Finding intersections

Recall the equation for a ray,

\[\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t) = \mathbf{c} + t(\mathbf{p}_{ij} - \mathbf{c}),\quad t\geq 0,\]and suppose we want to test for an intersection between \(\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t)\) and the image of some primitive under the transformation \(T\colon\mathbf{r} \mapsto M\mathbf{r} + \mathbf{b}\). Instead we do the following:

Transform the ray by \(T^{-1}\):

\[\begin{aligned} T^{-1}(\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t)) &= T^{-1}(\mathbf{c} + t(\mathbf{p}_{ij} - \mathbf{c}))\\ &= M^{-1}(\mathbf{c} - \mathbf{b}) + tM^{-1}(\mathbf{p}_{ij} - \mathbf{c}) \end{aligned}\]- Compute (as normal) the nearest intersection, \(\mathbf{r}_\text{int}'=T^{-1}(\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t_\text{int}))\), between the transformed ray, \(T^{-1}(\mathbf{r}_{ij}(t))\), and the primitive. Suppose the surface normal at the intersection point is \(\mathbf{n}'\).

Transform the intersection point and surface normal back by \(T\). This is easy for the intersection point:

\[\mathbf{r}_\text{int} = T(\mathbf{r}_\text{int}'),\]but the surface normal transforms more subtly:

\[\mathbf{n} = (M^{-1})^T \mathbf{n'}.\]See Wikipedia for a derivation of this so-called surface normal transformation.

This method is usually called instancing. The transformation in step 1 is said to go from “world space” to “object space”, and vice versa in step 3.

Implementation

Practically speaking, we implement transformations by first implementing an interface, Hittable, from which all primitives (and BVH nodes) derive. We can then make Transformation also a subtype of Hittable, constructed from some other arbitrary Hittable (to be transformed), along with the transformation to be applied. An important consequence of this architecture is that we can transform whole groups of objects (such as BVH trees) with a single transformation. This is both convenient for scene construction, and saves on run-time.

Another optimisation is that nested/chained Transformations (which arise often, because it is usually easier to conceptualise a transformation as a sequence of steps while designing scenes) should be automatically “squashed” into a single Transformation with the appropriate composite matrix and offset vector.

Finally, when transformations are used in conjunction with a BVH, we must take care to correctly update the bounding box of a transformed object. See this code snippet for an example of how this is done.

Solving the rendering equation

It’s useful to take a step back at this point to consider the problem of rendering more rigorously. Behind the scenes, a path tracer is really a Monte-Carlo integration approach to solving the rendering equation. Let’s discuss each of these terms in turn.

The rendering equation

Suppose we pick any point, \(\mathbf{x}\in\mathbb{R}^3\), on the surface of an object in our scene, and we want to know the amount and colour of light originating from \(\mathbf{x}\) in the direction, \(\omega_\text{out}\in S^2\), of our camera. We can decompose the outgoing light into its constituent wavelengths (ie. spectral colour), and ask about the intensity as a function of wavelength - the correct physical quantity for this is spectral radiance (aka. “specific intensity”), which is power per unit solid angle in the direction of a ray, per unit projected area perpendicular to the ray, per wavelength.

Hence, let \(L_\text{out}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{out},\lambda)\) denote the spectral radiance from \(\mathbf{x}\), in the direction \(\omega_\text{out}\) of the camera, of light with wavelength \(\lambda\). The rendering equation reads as follows:

\[L_\text{out}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{out},\lambda) = L_\text{emit}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{out},\lambda) + L_\text{ref}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{out},\lambda).\]Naturally, this expresses the outgoing radiance as a sum of that which is emitted by the material itself, and that which is reflected/refracted from light incident on \(\mathbf{x}\). The latter term breaks down further:

\[L_\text{ref}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{out},\lambda) = \int_{S^2} f_\text{r}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{in},\omega_\text{out},\lambda) L_\text{in}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{in},\lambda) \cos\theta_\text{in}\, d\omega_\text{in}.\]We integrate over incident ray directions (including those originating from below the surface, as from refraction or subsurface scattering), where the contribution from each direction includes the product of the incident spectral radiance, \(L_\text{in}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{in},\lambda)\), with the bidirectional reflectance distribution function, \(f_\text{r}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{in},\omega_\text{out},\lambda)\). Technically, to adequately account for refraction and subsurface rays, \(f_\text{r}\) ought to be a sum of the BRDF with the bidirectional transmission distribution function (BTDF); this sum is sometimes called the bidirectional scattering distribution function (BSDF).

The BSDF \(f_\text{r}\) is where we encode all of the (optical) physical properties of the material, such as albedo, colour, roughness, refractive index, and so on. Implementing a new material into our renderer therefore really just amounts to specifying \(f_\text{r}\). However it is implemented, it must obey the following requirements:

- Helmholtz reciprocity: \(f_\text{r}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{in},\omega_\text{out},\lambda) = f_\text{r}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{out},\omega_\text{in},\lambda)\)

- Energy conservation: \(\int_{S^2} f_\text{r}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{in},\omega_\text{out},\lambda)\cos\theta_\text{out} \, d\omega_\text{out} \leq 1\)

- Positivity: \(f_\text{r}(\mathbf{x},\omega_\text{in},\omega_\text{out},\lambda) \geq 0\)

Finally, also included in the integrand is a weakening factor, \(\cos\theta_\text{in}\), which is given by

This accounts for the fact that, for larger angles \(\theta_\text{in}\) between the incident ray and the surface normal \(\mathbf{n}\), outgoing flux is spread across a surface whose area exceeds its projection perpendicular to the ray.

Limitations of the equation

The rendering equation accounts for almost all real-world optical effects that we would want a renderer to capture. The only simplifications it assumes are commonplace within geometrical optics, and the phenomena it neglects are those involving the wave-like or quantum properties of light, such as:

- polarisation,

- interference,

- fluorescence,

- phosphorescence,

- non-linear optics,

- the Doppler effect.

These limitations notwithstanding, we expect the output of our renderer to at least approximately agree with a solution to the rendering equation.

Monte-Carlo integration

Suppose we were able to compute an exact solution to the rendering equation for each material in our scene. Our ray tracer would then not require bounces or multiple samples per pixel; we could simply fire one ray per pixel, find the point, \(\mathbf{r}(t_\text{int})\), where it intersects the scene, and colour the pixel using \(L_\text{out}(\mathbf{r}(t_\text{int}),\omega_\text{out},\lambda)\).

Our approach of firing many samples per pixel, having each one scatter multiple times randomly, is actually a (naïve) Monte-Carlo integration approach to solving the integral in the rendering equation. Recognising this is helpful because we can eke out some performance improvements by refining our Monte-Carlo method.

The general idea behind Monte-Carlo integration is that the definite integral \(\int_\Omega f(\mathbf{x})\, d\mathbf{x}\) of a (generally multivariate) function \(f\) over a domain $\Omega$ is closely tied to the average value, \(\langle f\rangle\), of \(f\) over \(\Omega\):

\[\langle f\rangle = \frac{\int_\Omega f(\mathbf{x})\, d\mathbf{x}}{\int_\Omega d\mathbf{x}}.\]While it may be hard to compute (even numerically) the definite integral, the average value \(\langle f\rangle\) is easily approximated by a discrete average,

\[\langle f\rangle \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N f(\mathbf{x}_i)\]over a sequence \(\mathbf{x}_1,\dots,\mathbf{x}_N\in\Omega\) of samples drawn uniformly from \(\Omega\). Explicitly,

\[\int_\Omega f(\mathbf{x})\, d\mathbf{x} \approx \left(\int_\Omega d\mathbf{x}\right) \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N f(\mathbf{x}_i).\]

Applying this to the rendering equation, we obtain

where the incident light directions \(\omega_\text{in}^i\) are drawn uniformly from the unit sphere.

Importance sampling

Importance sampling comes from the recognition that the uniform sampling of \(\mathbf{x}_i\) in the Monte-Carlo integration method is a special case of the more generic algorithm, where the samples are drawn from an arbitrary distribution \(p(\mathbf{x})\) over \(\Omega\). In fact, any distribution will work here, but some choices provide quicker convergence; this is the sense in which the choice of uniform sampling is naïve.

To update our formula for the case of an arbitrary distribution, note that if \(p\) is a uniform distribution on \(\Omega\), then \(\int_\Omega d\mathbf{x} = 1 / p(\mathbf{x}_i),\) for all \(\mathbf{x}_i\), so that our previous formula becomes

\[\int_\Omega f(\mathbf{x})\, d\mathbf{x} \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \frac{f(\mathbf{x}_i)}{p(\mathbf{x}_i)}.\]It turns out that this is the correct formula in the case of a generalised sampling distribution \(p\).

In general, we get the fastest convergence when shape of \(p\) more closely matches the (an appropriately normalised) shape of \(f\). Applied to our renderer, the technique of importance sampling allows us to bias our scattered light rays (off of any material) to favour certain directions, without affecting the physical accuracy of the final. Choosing certain scattering distributions will lead to faster convergence, meaning fewer samples per pixel will be needed for the final render to look good.

Generally speaking, we will want to bias scattered rays towards light sources in the scene, since a ray that fails to hit a light source before the bounce limit is exceeded will show up as an erroneous black pixel in the output. That said, we can also opt to send more rays towards anything we choose; other good choices are regions in the scene containing a lot of small details.

Actually, sorting this list is overkill. We need only partition our list into lower and upper halves, without requiring either half to be sorted. We can thus get better performance by only performing a partial sort, such as quickselect, which has linear average run-time complexity instead of the best-case of linearithmic for a sorting algorithm. ↩